The JAPAN TIMES WEEKLY

November 25, 1995 By John Cobb

Good friends clue us in to how our character is observed in the eyes of others. Often this is done through remarks on our personal effects and opinions like: "Aren't you tired of those glasses yet? " or "You must be stuck in the '60s since you still listen to that band." In the process, we get a chance to learn something about ourselves - sometimes painfully.

But when was the last time a friend described you as a swirl of multi-hued blue plunging into a fountain of bright orange? Or a universe of ripe red tomatoes floating around in your own space? That is what artist Sanae Takahata has achieved in Intimate Reflections 1991-1995: The Birth of a Self-Portrait, an arresting display of 17 large oil paintings showing at Sagacho Exhibit Space in Tokyo until the end of this month. Takahata has learned a lot about herself through the process of creating her works.

The artist's paintings capture the essence of each of her subjects at a particular time in their lives within the last four years. Some of the associations - one portrait includes family members - stem from the artist's childhood in Gunma Prefecture. Others are of friends made in far-away cities.

On the basis of these friendship bonds, Takahata gradually developed what became a bulging scrap book full of memorabilia on these meaningful people in her life.

In getting to know them better, she discovered important symbols in their lives, including other people, which she incorporated with different combinations of color to depict their dominant emotions. These she then melded into an inner portrait of each.

The result is a gallery of portraiture that drew this reviewer into certain of Takahata's works and repelled him from others. Each is so individualized that this makes sense. After all, we claim certain people as our friends for reasons having to do with affinities we perceive to have with them and tend to ignore others.

The artist's use of color and personal artifacts in the portraits was so disarming that I quickly felt after viewing each that I had suddenly been given a big dose of personal insight into the lives of each subject, even though I've never met any of them in my life.

This is no small trick to accomplish artisticallyCbut Takahata used her own method to make the idea work. She first created smaller works to translate her emotional sense of the subject into color, and then derived colorful abstract forms which she painted on and around the hyper - realistic rendering of each portrait in the large oils.

On a chair under each portrait at the exhibition one of these smaller palnt1ngs filled with swirls of colors rested.

The artist lost her self through her absorption in painting the portraits and by following the principle: "To know yourself is to forget yourself." "I have a plece of you, you have a piece of me," is the guiding idea behind her art.

Takahata started the four-year project by interviewing friends in Seattle, New York, Paris, Cuba and Japan. In the course of these meetings, she made a point of asking each two questions : "What makes you smile? " and "What keeps you going? "

Answers to these questions and others, along with the gifts in tbe scrap book, inspired the artist to keep working on the project, even through her own periods of self doubt. After distilling these feelings onto her canvases, Takahata titled each with a single trait that personifies an important aspect of each friend.

And although the subjects in the paintings. are quite personal to her, the feelings they evoke are universal.

The titles of the works provide a hook for the viewer to hang his hat on before settling in to muse on the details of each portrait. Thus in Independence (upper left), we get the idea that the person in Birkenstocks standing in the portrait gazing evenly back at us obviously thinks for herself. The simply dressed woman has a lightness of spirit made plain by the blue sky and white clouds transparently streaming through her smock to the horizon of some dry, sunnyland.

The woman's temperament is reflected, but What about those other details : the rolling pin and dough, the pen and paper, and that lanky guy mysteriously standing in the background? It turns out the woman is a former writer for the Asahi newspaper and that the man, her husband, works for the U. S. State Department. Takahata caught up with the friends in Cuba, which inspired the background for the portrait.

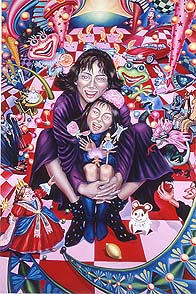

The artist's sister and then 4-year-old niece appear in Mischief (center). Her use of some art by the child in the portrait increases the sense of fun conveyed by the abundance of toys and their warm smiles.

Womanhood (lower right) mourns the loss of youth of the subject, a friend in her 50s bound by the traditional Japanese "ie" family system who must cook, clean and care for her father-in-1aw because she married the first son of the old man's family. The ripe tomatoes, reclined pose and darker colors convey a somberness about this time in the woman's life.

Not all of the subjects agree with the artist's vision of them. That's only human. The works succeed in making us wonder about them and ourselves.

The DAILY YOMIURI

November 3, 1995 By Joy Onozuka

In 1977, at the age of 18, Sanae Takahata bought a one-way ticket to Paris because she was convinced if she studied art in Japan it would kill her passion for painting. Almost a decade down the road, while living in Seattle, the introspective nature of painting drove her into a deep spiral of depression, crushing her passion for life.

"I wanted to blank out for a year-just go to sleep," she says.

Rather than seek counseling, she enrolled in art history classes. "In classes, I forgot about myself," she said. "I realized maybe there is no such thing as self. "

She began reading books on Zen andTaoism, and discovered a philosophy that dovetailed with her feelng that she needed to focus on life around her, rather than what was going on inside her head.

Drawing on the principle "To know yourself is to forget yourself," she began a four- year project interviewing people in Seattle, New York, Paris, Cuba and Japan who had influenced her in a meaningful way.

Because she had moved frequently during her 20s, Takahata says she had lost her roots. "I didn't feel that I belonged in one society, one country. I realized I belong with the people I met."

By retracing the paths of her friendships, she thought she could find pieces of herself.

The exhibition of her 38 oil paintings at Sagacho Exhibit Space in Tokyo is there- fore subtitled "The Birth of a Self-Portrait."

"Unlike most portraits that reveal the details of a person's face, Takahata's large- scale works are crowded with rich colors, objects and other people.

Possessions and clothing are important, says Takahata, because they reveal aspects of a person's character. "The body is a container for time and the spirit, while the house is a container for people."

The portrait of Claire, for instance, shows her wearing her favorite red dress, sitting with paintbrush in hand, in front of a picture of herself painting her sisters and mother, who sit cut off from each other around a table in New York.

In the upper right-hand corner is one of Claire's sons; below him, her husband and dog.

Like a puzzle, the images fit together snugly, representing a full, complex life rather than an isolated individual.

On a chair below the painting sits a small oil painting of circular ripples of gray, red, orange and purple. "Words don't mean so much to me," Takahata said. "Feelings take shape through forms."

The small painting is a preliminary work based on Takahata's feelings toward the individual. She calls the portrait of Claire "Hope" because that is what they share in common.

The simple labels, be it "Emancipation," "Mischief," "Creation," and "Harmony," and the cascading images trigger an avalanche of thoughts.

On one level, the viewer is challenged to piece together the images to form a story. On another level, they cause the viewer to think about whom they cormect with and why.

Not all viewers enjoy that aspect, though. "A man told me the works were difficult to look at because they naturally made him think about his life," she said, explaining the man lacked memories of much besides years of work.

Flipping through the slighty tattered project album, bulging with interview notes, photographs and sketches, Takahata seems to have collected all the critical pieces of her life.

"What's important in life is friends." Coming from Takahata, it's a statement that rings true.